Brainballs, Skulls and Warriors

(The Celtic Cult of the Head)

(Originally published at Imbolc 1996)

Eric Hobsbawn observed that the past is a foreign country and the world of the Iron Age Celts is now at least 2000 years distant from us. The worlds of Arthur and Myrddin, if one places them in historical terms, are roughly 1500 years from us. This is the ocean of time that Gary Oldman talked of in the film Bram Stoker's Dracula . Even a mere 20 years can demonstrate how time alters us and our perceptions. This gulf of time, however, needn't and indeed shouldn't put us off from attempting to understand and comprehend the wisdom and truth behind Celtic spirituality. This article will investigate the world of the Iron Age Celt in general and that strange beast the Cult of the Head in particular.

Eric Hobsbawn observed that the past is a foreign country and the world of the Iron Age Celts is now at least 2000 years distant from us. The worlds of Arthur and Myrddin, if one places them in historical terms, are roughly 1500 years from us. This is the ocean of time that Gary Oldman talked of in the film Bram Stoker's Dracula . Even a mere 20 years can demonstrate how time alters us and our perceptions. This gulf of time, however, needn't and indeed shouldn't put us off from attempting to understand and comprehend the wisdom and truth behind Celtic spirituality. This article will investigate the world of the Iron Age Celt in general and that strange beast the Cult of the Head in particular.

Delving into the cottage industry that is the literature on Celtic religion is not a job for the faint-hearted. You will find a number of agreed attributes. However, there is somewhat of a gulf between those who write for an academic audience and those who write for (shall we say) a pagan audience. Some but by no means all the agreed attributes vis à vis matters Celtic are: (a) The role of sacrifice - both human and otherwise (b) The role of the druids (c) Votive offerings, eg the offerings at the source of the Seine to Sequana (d) Multi-facetted and multi-functional "Godforms" (e) Belief in reincarnation (f) The Cult of the Head

This, of course, leaves out as much as it includes.

Major difficulties arise from the fact that there is no direct native literary witness who can discuss matters from the inside and this has allowed the shrouding of matters Celtic into a kind of impenetrable quagmire of delusion. It has allowed many who should know better to throw all manner of unrelated stuff into the "broth" and call it Celtic religion. Funnily enough, our very own special chum J R R Tolkein hit the nail right on the head when he remarked:

"To many, perhaps to most, people outside the small company of ..... scholars past and present "Celtic" of any sort is .... a magic bag into which anything may come .... anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight which is not so much a twilight of the Gods as of the reason."

The questions I have asked myself during my reading amongst others are: (a) Did the Celtic Cult of the Head exist? (b) If so, how was it manifest? (c) Does it have any relevance for us today? For Celtic spirituality?

My discussion is more of an exploration into what is known, a synthesis. My answers are not necessarily authoritative. Indeed it may be wise to state that perhaps there are no real "answers" to our posed questions.

The Modern Commentators

I will begin by chewing over a number of quotes ancient and modern. First - modern, with Ronald Hutton PCH (that's Pagan Culture Hero - Ed) in his tour de force The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: their Nature and Legacy (pp 194-5). Anyone who has heard the excellent Mr Hutton PCH, or read any of his oeuvres, will know that Mr Hutton does not pander to the memory of cherished misconceptions and he indicates that for him the idea of the cult should be set aside. He says:

"There is no firm evidence of a "Cult of the Human Head" in the Iron Age British Iles as was once asserted." and

"The frequency with which human heads appear upon Celtic metalwork proves nothing more than that they were a favourite decorative motif."

Hutton PCH (Pagan Culture Hero - Ed) poses a number of imponderables for us which are worth bearing in mind in relation to the ideology behind the whole beast. (a) Were the skulls found in pits originally war trophies? (b) Did they belong to human sacrifices? (c) Or to beloved members of a Family or Tribe? (d) Or to social outcasts not given normal burial? (e) Or even to individuals who needed special help to get free of their bodies after death?

The problem archaeologically-speaking is that the remains can be seen as either evidence of sacrifice or as war trophies, but they do not often unequivocally demonstrate a religious meaning - Hutton is surely right when he remarks that we "cannot tell".

This opinion of scepticism is echoed somewhat by Mr Iron Age himself, a certain Barry Cunliffe, who in his 900-page magnum opus jazzily entitled Iron Age Communities in Britain (3rd edition - retailing at £75) we find one relevant sentence for us (p519):

"Decapitation is .... more likely to have been a normal part of the battle scene than the presence of the priestly cult".

Anne Ross takes a significantly different line in her well-known Pagan Celtic Britain which is now 28 years old. She devotes 78 pages to the Cult of the Head and concludes (for our purposes p163 in my edition):

"The Cult of the Human Head .... constitutes a persistent theme throughout all aspects of Celtic life spiritual and temporal and the symbol of the severed head may be regarded as the most typical and universal of their religious attitudes."

This is clearly at some variance with the opinions above. Finally the excellent Miranda Green in her book The Gods of the Celts takes to my mind a middle way in this particular debate (p32):

"I refute any suggestion that the head itself was worshipped but it was clearly venerated as the most significant element in a human or divine image representing the whole."

This for the moment will suffice for our modern authorities save to say that there is some clear difference in opinion and emphasis which no doubt can be traced to the ambivalence of what remains to be studied and understood. The problems that they address concern "society" (a problematic term in Britain and Gaul 2000 years ago).

If we had the benefit of a time machine we might be able to solve some of the difficulties as we travel back to the Celtic lands. What would we find?

First of all however there is, I should say, some debate about whether we can use the term "celtic" and whether those we happily call Celts called themselves Celts. Strangely enough a man I love to hate helps us out here with a remark in his De Bello Gallico . C Iulius Caesar says:

"Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres .... tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra galli appelantur" , or:

"Gaul is divided into three parts ... the third called in their tongue Celtae and by us Galli"

Can this little observation at the beginning of Book I allow us to extrapolate a wider Celtic identity at this time? If we return to our thoughts of what we would find on landing in our time machine, I think one of the noticeable elements would be that society in Britain and Gaul was a tribal one. Later on this allowed the Romans to play on the rivalry of the élites of the Trinovantes (of modern Essex) and the Catuvellani (of the southern Midlands and the south east). It follows, I would suggest, that a unified understanding of matters religious is not necessarily the case. Tribal identity is foremost, only then followed by a more broad, a vaguer identity which despite a certain je ne sais quoi was manifest on a number of occasions. It is therefore unwise to see all Celtic "Godforms" as recognised and venerated by all "Celtic" tribes just as it is wrong in my view to invest the Immortal Celtic Gods with pantheon-style attributes set in stone and sadly known to us all too well, eg the portrayal of the Greek divinities in flimsy Hollywood films, for example Clash of the Titans .

One of the most enduring attributes of the Celtic Gods is that they "change" and are not "static".

There are, as a short visit in the time machine would show, important similarities as well, eg the worship of Lleu or Lugh is attested by place name evidence from places as far apart as Lugudunum (modern Lyons in France) to Luguvalium (Caer Lliwelydd - modern Carlisle). It follows therefore that the same should be observed for the Cult of the Head, the practices and ideas of the Salii or Saluvii of modern Provence do not correlate necessarily with those of the Ulaidh-tir of modern Ulster.

BUT

Having taken this on board alongside some sensible caveats, maybes and probabilities, let's go and meet some authorities from the past!!

The Classical Commentators

As far as Britain and Gaul are concerned, as I indicated earlier there are no native writers. However we can dip our toes into the baths of a number of classical writers, but it is always important to keep at the forefront of our minds that these writers were not Celtic and viewed matters from an alien viewpoint - one that they would term "civilised". Chief amongst them are: (a) Diodorus Siculus (b) Strabo (c) Livy (d) C Iulius Caesar

Livy, our third chum, records the placing in a temple of the head of a prized enemy chieftain by the Boii. He also records of the Boii, who lived in northern Italy, their custom of adorning skulls with gold and using them as cups for pouring libations. He records that in 216 bce a Roman general called Postumius met his end at the hands of the Boii. After he was killed they:

"stripped his corpse, severed the head, and bore their prize in triumph to their most sacred temple. There, according to their habit, they cleaned it, decorated the skull with gold and employed it as a sacred vessel for the pouring of libations for the priests and acolytes of the temple to drink from."

Livy also recalls the Senonian Gauls who after the battle of Clusium in 295 bce collected the heads of the fallen.

Diodorus Siculus and Strabo also record the custom of embalming the heads of their most reknowned enemies in cedar oil. These were then preserved in a chest and exhibited to strangers with great pride as insignia of military prowess. Apparently their owners often refused to part with them even for their weight in gold, so highly were they esteemed.

Finally, we have the witness of one writer who travelled extensively in Gaul and visited Britain on two memorable occasions - a certain Caius Iulius Caesar. Despite Michael Richter in his Medieval Ireland I have failed to find any reference to head hunting or the Cult of the Head in his De Bello Gallico . Despite a rather in-my-face creature at the Chesterfield Pagan Federation Conference I am still convinced that this absence is significant. Caesar was writing a piece of propaganda in De Bello Gallico on a number of varied levels and our Iulius does not generally avoid the opportunity to point out the depravity of his opponents and the glories of Senatus Populusque Romanis. I let you draw your own conclusions.

Likewise, in respect that both Livy and Diodorus Siculus acquired all their information on matters Celtic from indirect sources (principally a certain Poseidonius whose main interest was the south of Gaul which itself was influenced by the Greek colony of Massilia, the modern Marseilles). So we are forced to take what is told to us by our classical chums with a lorry-load of salt.

The Mythological Evidence

The best thing to do would be to consult the Celts themselves .... and the next best thing for us is to consult the ancient mythologies. In these we can find a number of interesting stories. The first vignette of evidence that I shall present is from the Taín Bo Cualinge , called in English The Cattle Raid of Cooley . Principally this epic saga concerns the exploits of Cú Chulainn with roles from Conchobhair Mac Nessa, king of the Ulaigh who resided at Emhain Mhacha, the heroes Conall Cernach, Fegus Mac Roich, the troublemaker Bricriu and the druid Cathbhadh. The action revolves around a conflict between the Ulaidh-tir and the Connachta for the Dunn Cualinge, the Brown Bull. At a pivotal point the Ulaidh-tir are laid low by a debilitating sickness and Cú Chulainn is forced to stand alone. He defeats all who come against him but ultimately dies of his wounds. The passages from the Taín indicate the importance of head collection:

(Page 73, Kinsella)

"The warriors Err and Innel and their two charioteers Foich and Fochlam came upon him. He cut off their heads and tossed them onto the four points of the tree fork." and

(Page 166, Kinsella)

"When they found him they fought foul and fell on him all 12 together. But Cú Chulainn turned on them and struck off their 12 heads. He planted 12 stones for them in the ground and set a head on each stone."

A further Erse story is the Scéala Mucce Meic Da Thó or The Story of Mac Da Tho's Pig . This concerns a feast prepared by Mac Da Thó, king of the Laigin-tir (Leinster) for the Ulaidh-tir and the Connachta (see Knott and Murphy, Early Irish Literature p 122). Both Ailill and Medb on the Connachta side and Conchobhair mac Nessa on the other asked Mac Da Thó for a famous hound he possessed but he had managed to promise the dog to both. Down at the feast the main part of the vitals was a portion of a pig. The question was asked how the pig should be divided and Bricriu suggested that it be divided "in accordance with battle victories (ar chomramaib) ".

This sets the scene for a series of boasts and taunts culminating in a battle between Cet the Connacht champion and Connal the Ulaidh champion. Connal says at this juncture:

"I swear by that by which my people swear since I took spear in hand I have never been without slaying a Connachta man every day and plundering by fire every night and I have never slept without a Connachta man's head beneath my knee."

Later, as you would expect, there is a battle, and the Ulaidh obtain the hound which meets a painful end impaled on the shaft of Ailill and Medb's chariot.

The significance of the head in another manner is shown in a story of the Mabinogi which I am sure many readers will know. Briefly then, this story is called Branwen, Daughter of Llyr and recounts the story of Bran or Bendigeidfran (Blessed Raven) who at one point in the story commands that his head be struck off:

"And take the head he said and carry it to the White Mount in London and bury it with its face towards France."

This is later known as one of the Three Unhappy Concealments before forming one of the Three Unhappy Disclosures.

Archaeology

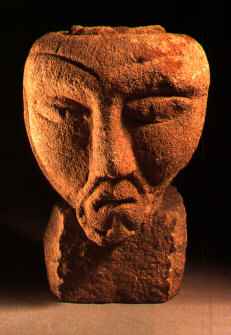

The final strand in my investigation involves the dry bones of archaeology. The most famous sites are both in Gaul. At Entremont in Provence a Celtic tribe called the Salii or Saluvii constructed a shrine at which when the Romans routed the tribe in or around 125 bce they found assorted statues. One pillar displays mouthless faces with closed eyes. Also extant were remains of human heads. Several adult male heads had been cut from dried bodies, some with curly head, some still bore the nails with which they had first been fixed to wooden posts elsewhere.

Nearby in Roquepertuse by the mouth of the River Rhône stone pillars beneath a lintel contained skulls and severed heads. The central lintel is surmounted by a bird figure which is usually said to be that of a goose (does anyone know of any myths that relate death to geese?). In front of these lintels there are two squatting fitures which were originally painted. The skulls here are the skulls of men in the prime of life. One of them even has a javelin head embedded within. There is little extant in the same line in Britain but there are a few smaller scale examples (though absence in archaeology does not indicate absence in the past). A similar shrine at Cosgrove in Northamptonshire is rectangular and "simple", possessing one human head buried in one wall.

Further evidence in stone is furnished from Trajan's column which shows Celts riding home from battle with the heads of their defeated enemies. Other evidence comes from the Pfalzfeld stone pillar (Germany) of the C4th or C5th bce which bears human heads on each of the four sides. There is a cornucopia of images.

Anne Ross in her Pagan Celtic Britain has divided the images into various forms:

Anne Ross in her Pagan Celtic Britain has divided the images into various forms:

(a) Multiple Heads

The interesting heads of the Remi tribe who lived around modern Rheims often portrayed tricephaloi (and used by John Boorman in Excalibur (sic) when Merlin (sic) spoke to Morgana (sic) of the passing of the Old Ones). Examples from Britain are rare but Mercia has one example from Viroconium, now known as Wroxeter though at the time it has more connection with the Welsh polity of Powys. (see p111)

(b) Horned Heads

Evidence for the worship of a horned God in Europe and Britain (Cernyn) is strong. Images that survive show a distribution pattern that favours Hardian's Wall but may reflect the vagaries of modern archaeology more. The distribution map in Ross (p173) has one example in Mercia and one in Lindsey.

(c) Heads without Attributes

A category for stone heads that are significant of deity itself. Ross describes one example from Towcester in Northamptonshire and one from Oadby in Leicestershire, now in the Leicester museum. (p 124)

(d) Gorgon Heads

Despite the misuse of the classical name Gorgon these heads appear to be cognate with Green Man images. The one illustrated comes from Bath.

(e) Phallic Heads

A potent combination suggesting perhaps that for the Celts the head was the centre of the life force capable of continued independent life after the death of the body. Examples are numerous but include an example from Broadway in Worcestershire. (see p 107)

The practice of representing a God by the Head alone appears to be the result of a complex series of thought processes. Celtic deities are less bound by functional definition than their Graeco-Roman counterparts became, thus overt identification in images was less important.

Additionally, the head image had other properties; set against the background of ritual it could represent the God pars pro toto (ie a part representing the whole) - thus the power of the image would have been positively enhanced because the symbolism was concentrated on the part of the body considered most important. Portrayal of the divinity by a head alone may thus have been a deliberate method of honouring the Gods.

Conclusion

We have come some way in this exploration and there are many strands to pull together to create the weave. Can I attempt any meaningful conclusions? I set out with the prejudice that the Celtic Cult of the Head did not exist as a homogenous entity. Now I am not so sure. Perhaps the root of the problem lies in the name itself, this being perhaps a misnomer. It might be a little boring and it will undoubtedly affect the frisson that surrounds the Celts but I think it is worthwhile to be as accurate as possible. The Celts were not mere head hunters as a one dimensional reading of the evidence would suggest. They clearly carried their reverence beyond this, perhaps believing that the head was the seat of the soul, the essence of the human. Whatever one says, the cult importance of heads manifests itself but if we ask "why?" I think the true answer is that there can be no answer. And what of today's pagans? Does any of this have any significance for us? That is, once again, a very difficult imponderable but may touch upon whether we feel our Gods and Goddesses may be relevant today. They are to me, but I do not especially feel the urge to go a-head-gathering. Mystery, then, clouds the Celtic Cult of the Head, but to me there is no wrongness in mystery - only beauty.